Blacks have always been at the foundation of the Christian faith and were Christians before Europeans ever even heard of Jesus. As the scriptures recall in Acts of the Apostles chapter 10, it was a very reluctant Simon Peter who had a vision to go visit Cornelius, the Roman military captain, and introduce him to Christ. Captain Cornelius and his household would later become the first European (Gentile) converts to Christianity, the Bible attests.

Gospel writer and evangelist John Mark, a wealthy African – probably from Cyrene and descended from the tribe of Levi – is credited with establishing one of the very first Christian churches, now known as the Coptic Orthodox Church, in Alexandria, Egypt, back in A.D. 42.

Blacks have always been in the forefront of the Christian movement. They were among the original disciples, the propagating apostles, the rooted patriarchs, and the trailblazing pioneers – and they were among the great reformers and revolutionaries.

Athanasius of Alexandria was one such giant. Although short in physical stature, Athanasius the Great was the “Pope of North Africa” and stood strong in his advocacy for a Bible-based theology. This was, of course, at a time when heresy was rampant in the evolving church of the fourth century. A contemporary of Emperor Constantine the Great, the First Council of Nicaea, and the period of Arianism, this senior Catholic bishop was exiled five times by Roman emperors and collaborating popes for his firm stance on Trinitarianism and many core doctrines that are now foundational to Christianity. It was Athanasius who first chronicled the 27 books of the New Testament scriptures and is a father of “Black Preaching.”

As we fast track to more modern times, Blacks in America only began to regain ecclesiastical leadership in the church in this post-slavery era. Slavery was a dark period in the Christian faith, and most churches and denominations were not welcoming to Blacks. Church pulpits were well out of reach during a time when Black people were only allowed to sit in the back of Christian churches, climb their way to the balcony, or stand outside. A movement would brew from this un-Christlike practice, and many enslaved and freed Africans – humiliated into worshiping the same God in inhuman ways – would leave these churches to establish their own.

Heavily discriminated against by their fellow White Christians, a group of free Blacks left the John Street Methodist Church in New York City in 1796 to form their own. For many years, they were served by White Methodist ministers until the election of their first Black clergyman, Bishop James Varick.

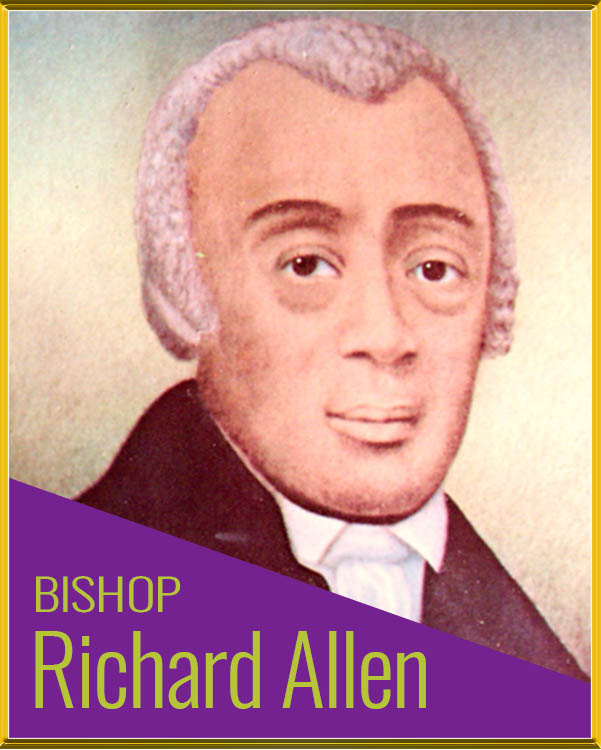

South of New York City in the city of Philadelphia, the Free African Society (FAS), established by Rev. Absalom Jones, Rev. Richard Allen, and others, was engrossed in a movement towards spiritual dignity. Pulled from their knees by church officials while praying at the St. George’s Methodist Church, they were pressed to form their own congregation, and the Bethel AME Church was established in 1794 with Allen as their first pastor. That movement would grow to become the third largest Black denomination in America.

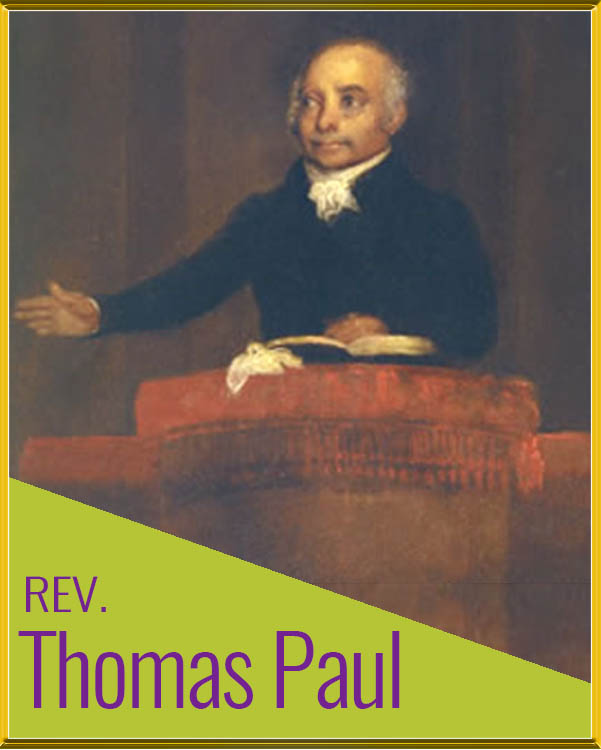

Harlem’s Abyssinian Baptist Church, once America’s largest congregation, has a very similar history to that of Bethel. Forced to sit in the back and to climb on ladders to the balcony, a group of Black worshipers left First Baptist Church in New York City in protest. With the assistance of Rev. Thomas Paul of the African Baptist Church in Boston, they formed Abyssinian.

Paul was one of the first Blacks to be ordained a Baptist in America, and he founded one of the first “Black-led” churches in the North. He would help to shape Black Liberation Theology and Black preaching.

This report lists 20 key and strategic Black preachers and theologians who were the first Blacks to be ordained or to play lead roles in America’s Christian denominations.

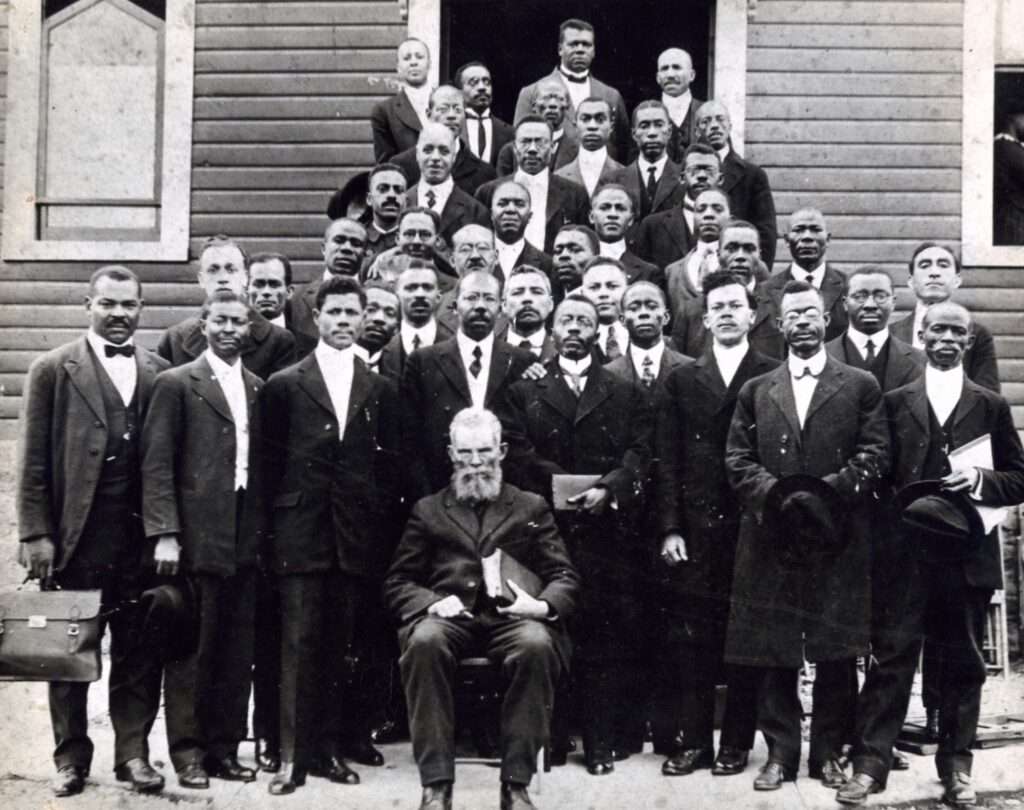

CAPTION 1: Pastor Charles Marshall Kinny (seated) with most of the earlier Black pastors in the Seventh-Day Adventist Church.

CAPTION 2: Athanasius the Great, the “Pope of North Africa”

Bishop Richard Allen was born on February 14, 1760, on the Delaware property of Benjamin Chew. Allen was born into slavery and was not exempt from the harsh treatment slaves had to endure.

Seeing the cruelty perpetuated by the slave masters, he was moved to become active in the Philadelphia abolitionist movement.

Encouraged by his unconverted enslaver to attended meetings of the local Methodist Society, Allen taught himself to read and write, joined the Methodists and started evangelizing at the age of 17. Allen’s master was eventually persuaded that slavery was wrong and offered enslaved people an opportunity to buy their freedom. Allen performed extra work to earn money and bought his freedom in 1780, changing his name from “Negro Richard” to “Richard Allen”.

In December 1784, he was appointed as a qualified preacher at the famous Christmas Conference, the founding and considered to be the first General Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church in North America. He was one of the two Black attendees of the Conference, along with legendary Harry “Black Harry” Hosier, but neither were allowed to vote during deliberations.

Two years later, in 1786, Allen became a preacher at St. George’s Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia, but was restricted to only conduct segregated sermons. As he attracted more Black congregants, the church vestry ordered them to be segregated in a separate area for worship. In protest in 1787, Allen and Absalom Jones led the Black members out of St. George’s and they formed the Free African Society, a non-denominational aid society that assisted fugitive enslaved people and new migrants coming into the city of Philadelphia.

While they remained friends and colleagues, Allen and Jones parted ways religiously. In 1794, Allen founded the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME) and in 1816, he was elected as their first Bishop.

Rev. Thomas Paul was born September 3, 1773, in what was then the province of New Hampshire. He was the son of a freed slave and was well versed in his academics. He would go on to higher education in the field of ministry.

After marriage, Paul moved to Boston where he joined the First Baptist Church. The interracial (Black & White) congregation was challenging for Blacks due to discrimination perpetrated by White officials and church members. For this reason, Paul and 20 other Black congregants started their own church named The First African Baptist Church.

Rev. Thomas Paul became the first pastor of the church and soon thereafter baptized over one hundred new members. He would often merge Bible teachings and social justice, and was also an advocate for African Americans to gain equal acceptance in society. Rev. Paul was also instrumental in the formation of Abyssinian Baptist Church in New York City.

Preacher Harry Hosier was born in 1750 and was known generally as “Black Harry”. Since he had no access to formal education, he habitually misspelled his name, so it is variously recorded as Hoosier, Hoshur, and Hossier.

With no authentic record to prove the exact location where he was sold, it’s assumed to be Baltimore, Maryland, which was just a stone’s throw from a prominent Methodist church. It was there that Hosier providentially met Bishop Francis Asbury, the “father of the American Methodist Church”, who subsequently offered him a job as his carriage driver and servant.

Bishop Asbury discovered that despite being illiterate, Harry possessed a remarkable ability to memorize long passages word-for-word, and he used Harry to warm up the crowds for sermons.

In 1781, Hosier gave his first sermon entitled “The Barren Fig Tree” in the Black Methodist Congregation at Adams’s Chapel in Fairfax County, Virginia. He was often called the best orator in America but was never formally ordained by the Methodist Episcopal Church.

Rev. Lemuel Haynes was born on July 18, 1753, to an African American man and a White woman. He was turned over as an indentured servant at the age of 5 months to Deacon David Rose, a blind farmer.

Haynes became conversant with bible teachings when accompanying Rose to church. He ended his indenture at the age of 21 which became a great opportunity for him to vehemently kick against slavery by writing extensively for its abolition.

During the American Revolution, he served in the military. Upon returning home after completing his military service, he decided to study theology with members of the clergy in Connecticut and Massachusetts. He was granted a license to preach in 1780 by Reverend Daniel Farrand, and in 1785, he was ordained in the United States, without a debate, remaining at Hemlock Congregational Church.

Haynes is recognized as the first Black man in the United States to be ordained as a minister. In 1804, he became the first African American to receive an honorary masters of arts degree. Haynes was the first Black abolitionist to reject slavery on purely theological grounds, and he constantly wrote and spoke of its abolishment, establishing him as one of the founding fathers of Black Liberation Theology.

Born in 1750, George Liele was sold into slavery in 1752 in Virginia and later taken to Georgia. His master, Henry Sharp, was a deacon in Rev. Mathew Moore’s church, and Liele was converted in 1773 under Rev. Moore’s ministry and was licensed to preach that same year, the first African American to be so.

Worshipping in the midst of the Whites was quite challenging but Liele did not grimace nor lament; he patiently complied to every instruction. As a devoted young man, he used any available opportunity to preach to other slaves.

After receiving freedom from slavery, he migrated to Savannah, Georgia, and assisted in organizing an Baptist church. Later, he migrated to Jamaica – making him the first American missionary and the first Baptist missionary in Jamaica. His first sermon in Kingston gained wide attention and attracted a huge audience. He gathered a congregation, bought a piece of land and built a chapel, establishing the Ethiopian Baptist Church of Jamaica. In 1773, he founded the First African Baptist Church in Savannah, Georgia, now the oldest Black church in North America.

Absalom Jones was born into slavery on November 7, 1746 in Delaware. He served as a merchant in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, but was permitted to attend Benezet’s School where he learned how to read and write.

A few years after his marriage in 1770, Jones joined the interracial congregation of St. George’s Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia and was appointed as a lay minister. During this period, Pennsylvania had abolished slavery but members of the church still indulged in racial discrimination. This caused Jones to unite with Richard Allen to form The Free African Society (FAS). Jones began to hold religious services at FAS, and shortly thereafter petitioned to establish an African American congregation that would remain a part of the Episcopal Church but without Caucasian control. His petition was accepted and Rev. Absalom Jones was ordained as a deacon in 1795 and a priest in 1802. He was the first African American priest in the Episcopal Church.

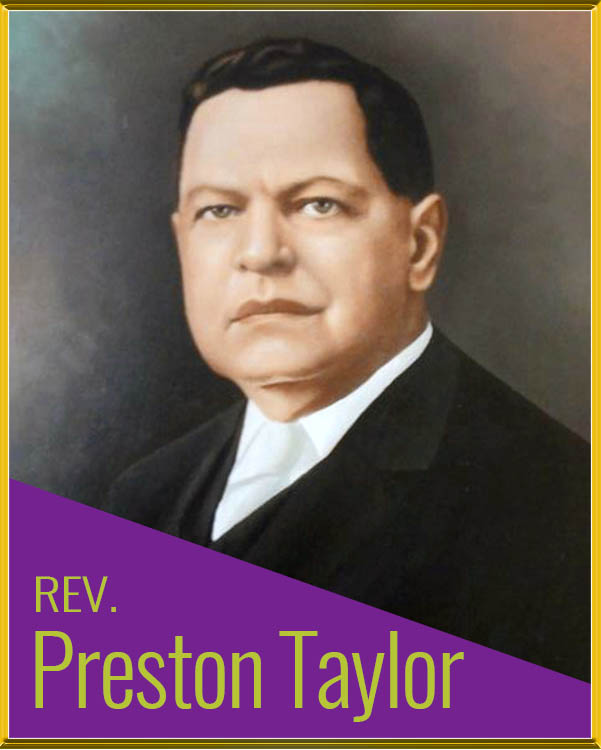

Rev. Preston Taylor was born into slavery in Shreveport, Louisiana, on November 7, 1849. At the age of four after attending a sermon in Lexington, Kentucky, Preston boldly expressed to his mother his desire to become a preacher.

Preston gained his freedom in 1865. He became a marble engraver and decided to relocate to Louisville, Kentucky. However, the White residents refused to work with him. After deep contemplation, he took a job as a Train Porter, working for the Louisville & Chattanooga Railroad for four years.

After resigning from the railroad, Preston was called to become a pastor and minister with the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). In 1874, he founded the High Street Christian Church, and it became the largest congregation in the state. In the mid-1880s, Rev. Taylor bought college property to build Christian Bible College for the education of Blacks at New Castle, Kentucky.

He moved to Nashville in 1884, and soon emerged as one of the city’s most influential African American business and religious leaders. He was involved in multiple business ventures, including the first Black bank, foundation of what is now known as Tennessee State University, the establishment a mortuary and the Greenwood Cemetery, and in 1905 he developed Greenwood Park, a 37.5 acres recreational park for the Black residents of Nashville who were not allowed to utilize public parks at that time.

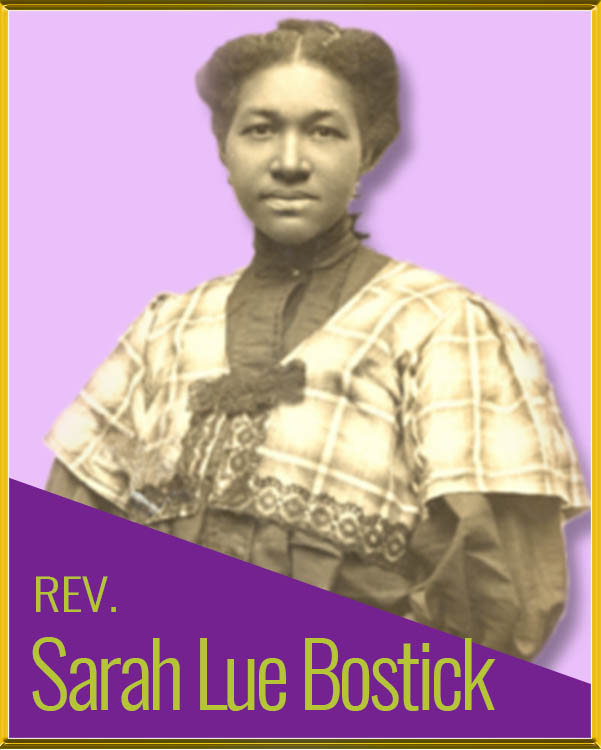

Rev. Sarah Lue Bostick (neé Howard) was born on May 27, 1868 in Glasgow, Kentucky. She was a key organizer of the first African American Christian Women’s Board of Missions (CWBM) auxiliary of the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) in 1892.

A hard-working and dedicated woman, Sarah is well-known for being the first African American woman ordained within the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). She travelled extensively, preaching and helping to establish missionary boards and auxiliaries throughout Arkansas, Missouri, Tennessee, Kansas, Texas and Oklahoma.

As a kind-hearted woman, she made bonnets by hand and donated the earnings to support a host of missions, including the African American Christian Women’s Board of Missions (CWBM) – which she played a jey role in organizing, the Southern Christian Institute, and Disciples missions to Jamaica.

Sarah and her husband Mancil Mathis Bostick founded the Mount Sinai Christian Church in North Little Rock, Arkansas.

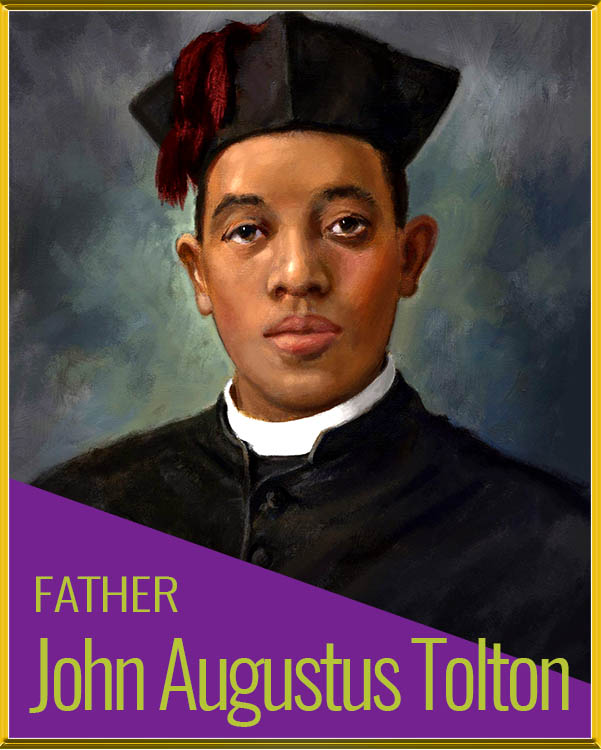

Father John Augustus Tolton was born on April 1, 1854. Tolton and his family escaped slavery from Missouri and resided in Quincy, Illinois.

Albeit being educated, multilingual and supported by local Irish and German-American priests, who believed in his priestly vocation, Tolton was rejected by every North American major seminary to which he applied.

Due to being resilient and determined to serve as a missionary, Bishop Peter Joseph Baltes arranged for his reception into the Pontifical Urban University in Rome, and Tolton was ordained on April 24, 1886 at the age of 31. He was assigned to the United States as a missionary to his fellow African Americans.

Tolton served as the first Black Catholic priest in the United States. He conducted his first mass in the U.S. on July 18, 1886 at St. Boniface Catholic Church in Quincy, Illinois. His attempts to organize a parish there proved futile because of White opposers. Finally after being reassigned to Chicago, Father Tolton opened St. Monica Church in a storefront and the church was dedicated on January 14, 1894, the first Catholic church in Chicago built by Blacks for their own use.

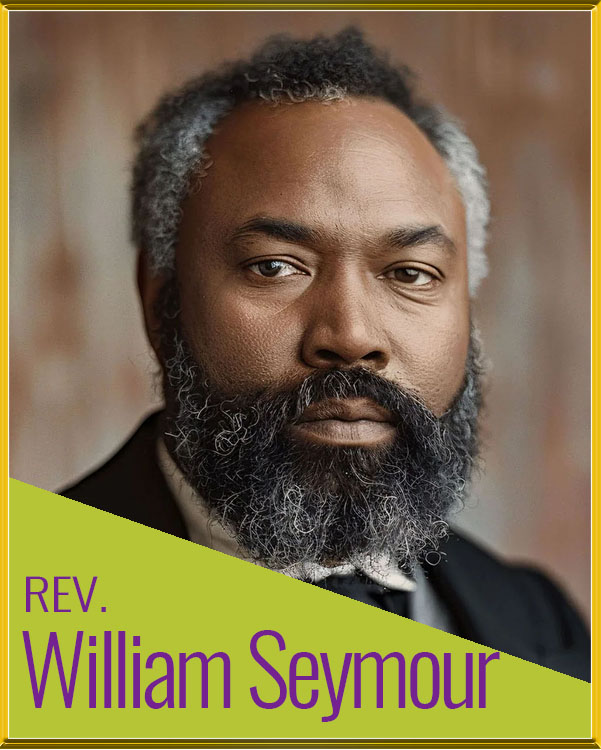

Rev. William Joseph Seymour was born on May 2, 1870. He became a born again Christian in the Simpson Chapel Methodist Episcopal Church in 1895 and met Pentecostal minister Charles Parham, who led a growing movement in the Midwest. As a student of Parham, he adopted Parham’s belief that speaking in tongues was the sign of receiving Baptism of the Holy Spirit.

When Seymour moved to Los Angeles, California in 1906, he preached the Pentecostal message which led to the Azusa Street Revival, drawing the attention of many believers as well as media coverage focusing on the religious practices as well as the racially integrated worship services, which went against the racial norms of the time. The resulting movement became widely known as Pentecostalism and by the end of 1909, every region of the U.S. had a Pentecostal presence, with additional missions planted in 50 nations worldwide.

After several years of partnership, his relationship with Parham ended over theological differences. Despite all odds, Seymour remained pastor of the Apostolic Faith Mission, which also became known as Azusa Street Mission, until his death.

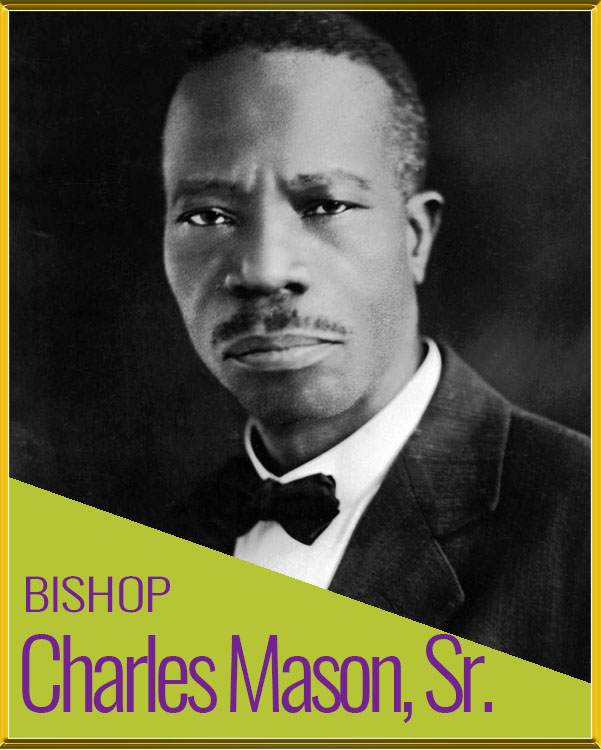

Bishop Charles Harrison Mason, Sr. was born on September 8, 1864. As a little boy, he was greatly influenced by the religion of his parents and joined them in attending the Missionary Baptist Church in Shelby County, Tennessee.

Throughout his childhood, Mason strongly opposed pursuing ministry as a clergyman, only wanting to remain a church lay member. Surprisingly, he got baptized by his older half-brother, Rev. I. S. Nelson, at the age of 15 due to experiencing God’s healing hands when he miraculously received healing from tuberculosis disease. At his moment of healing, he knew God had called him to service!

In 1893, at the age of 27, Mason began his personal ministerial career by accepting a local license from Mount Gale Missionary Baptist Church in Preston Arkansas. He enrolled at the Arkansas Baptist College, but withdrew after three months because he was dissatisfied with the teachings, curriculum and methodology of the college in Arkansas, believing that the teachings were too liberal and did not have a strong enough emphasis on the Word of God.

In 1895, Mason became acquainted with other preachers who shared his enthusiasm for Holiness teachings, and in 1897 they founded the Church of God in Christ (COGIC). He was sent by the church to Los Angeles to investigate the Azusa Street Revival, and his stay lasted 6 weeks. Before it was over, he experienced the baptism of the Holy Ghost and spoke in tongues. After his experience, he established a new Pentecostal group in Memphis and established it as the headquarters of COGIC. He served as Senior Bishop of COGIC for 54 years.

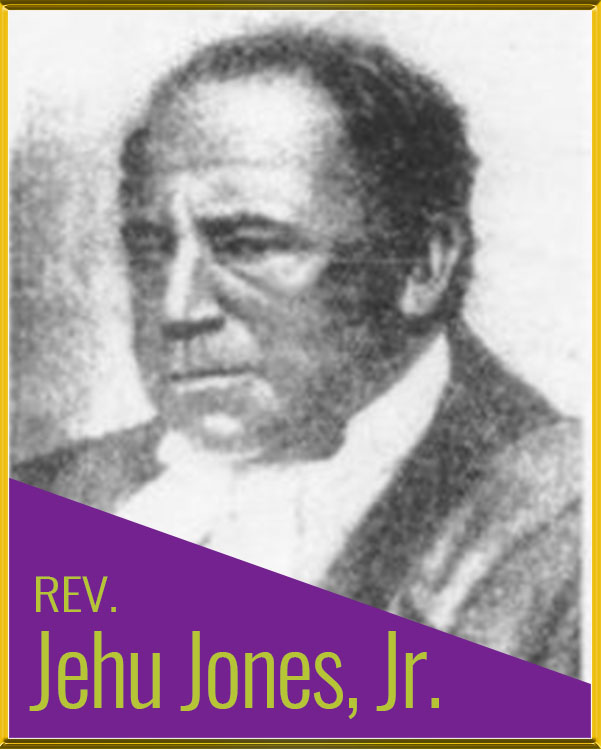

Rev. Jehu Jones, Jr. was born in the year 1786 as a slave. His father, Jehu, Sr., was a tailor and bought his freedom (along with that of his wife, Jehu’s mother) in 1798, liberating the children from slavery.

Jones was introduced to the doctrine of the Episcopal Church but diverted to the Lutheran Church, becoming a member of Charleston, South Carolina’s St. John’s Lutheran congregation in 1820. He was ordained as a missionary in 1832 through the encouragement of his pastor, Rev. John Bachman.

In 1832, Jones travelled to New York for ordination as a missionary, having accepted a job in Liberia to work with freed slaves who emigrated to the new nation. However, he didn’t make it to Liberia because upon his return to Charleston, he was jailed for violating South Carolina’s new law which prohibited free Black slaves from returning to the state.

After his father’s death and his own release from jail, Jones took his inheritance and moved to Philadelphia. As a Lutheran minister, he founded one of the first African American Lutheran congregations in the United States, remained active in Pennsylvania politics and was devoted to improving the social welfare of Blacks.

Rev. Ellsworth S. Thomas was born into a family of freed slaves in New York in March 1866. He was a laundryman and a laborer, as indicated by the Binghamton city directories from 1888 to 1892. He holds the distinction of being the first African American to hold Assemblies of God ministerial credentials.

Starting in 1899, he was listed in the city directories as a travelling evangelist. His name first appeared in the Assemblies of God ministers’ directory in October 1915, which stated that he was a “colored” pastor in Binghamton. When told to re-submit credentials in 1917, Robert Brown, the influential pastor of Glad Tidings Tabernacle in New York City, endorsed the application, and Ellsworth confirmed he was ordained on December 7, 1913 by Robert E. Erdman.

From 1917 to about 1922, records revealed that Rev. Thomas pastored a congregation in Beaver Meadows, New York, and remained an AG evangelist in the Binghamton area for the remainder of his life, known for his Bible teaching and good cheer despite the obstacles he faced, including partial blindness. He never pastored a large congregation, but he was faithful where God placed him. A photograph of Rev. Thomas has never been located.

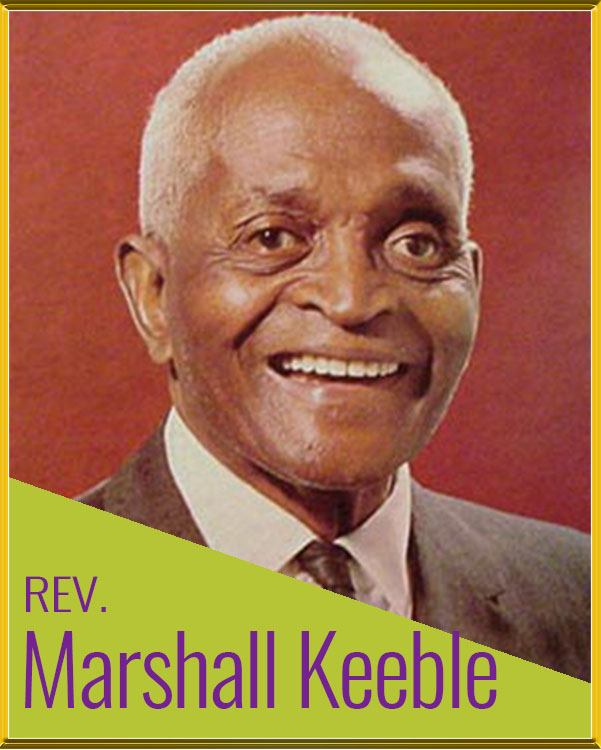

Rev. Marshall Keeble was born on December 7, 1878 in Murfreesboro, Tennessee. He was academically ignorant but still persevered to become an entrepreneur and an accomplished debater.

In 1897, Marshall started preaching through the support of his father-in-law, S. W. Womack, and other preachers. Despite managing several businesses, he put all of it aside in 1914 and focused on preaching.

In 1918, he assisted in starting a congregation of African American members of the Church of Christ, which he did on several occasions as time went on. While many of his White brethren donated money, time and resources to support his preaching and travels, they also did not challenge the segregation of congregations. He refrained from speaking publicly on matters of racial inequality and thus ensured he didn’t’ lose the support he needed from White brethren to get the message out to the African American population.

In 1942, Reverend Marshall Keeble became the founder and first president of Nashville Christian Institute. Applaudably, it is estimated that he baptized 40,000 people around the globe, and also he succeeded in setting up many schools like Southwestern Christian College and West End Church of Christ Silver Point.

Rev. John Gloucester was born in Kentucky in the year 1776 as a slave named Jack. He was the first African American to become ordained as a Presbyterian minister in the United States. Rev. Gideon Blackburn, a Presbyterian minister and ardent evangelist among the Cherokee Indians in Tennessee, bought Jack and taught him theology before freeing him in 1806 at the age of 30. Rev. Blackburn was able to get Jack’s name changed to John Gloucester and successfully authorized him to preach the Presbyterian faith “to the Africans.”

By 1807, Gloucester began street preaching in Philadelphia. He returned to Tennessee to obtain his license to preach and was ordained as a minister – the first African American to become an ordained Presbyterian minister in the United States. While preaching in Philadelphia, his wife Rhoda and their four children were still being held in bondage in Tennessee. He was eventually able to raise $1500 to free his family from slavery, and they were brought by wagon from Tennessee to Philadelphia in 1810 by his former master, Gideon Blackburn.

Rev. John Gloucester founded the First African Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia and began preaching at a house on Gaskill Street until his congregation grew and was able to build a church in 1811. He preached his first official sermon to a congregation of 123 people, serving there until he died of pneumonia in 1822.

Pastor Charles Marshall Kinny was born a slave in the year 1855 in Richmond, Virginia. At the age of ten, he started supporting himself by doing odd jobs.

In 1878, he attended a series of evangelistic lectures by J. N. Loughborough. The messages changed his mindset as he came to realize that God loved and cared about him. A guest speaker, Ellen G. White, delivered a powerful and unforgettable sermon which Kinny took to heart. What he learned moved him to get baptized as a Seventh-day Adventist in 1878.

Even though there is no proof of academic prowess, after his baptism, the 23-year-old Kinny was trusted with the responsibilities of the church clerk – and he proved to be an excellent record keeper and statistician, meticulously producing the quarterly reports of the Nevada Tract and Missionary Society. His dedication and devotion to the work fetched him the opportunity to attend college through the help of several local church members.

Charles Kinny was ordained on October 5, 1889 as the first Black Seventh-day Adventist Minister. He was instrumental in organizing a number of Black SDA churches, and he was known to be the pioneer of the Black (regional) conference concept, earning him the title as the “Founder of Black Adventism”.

Rev. John Andrew Buckley was born on the 20th of October, 1818, in St. John’s, Antigua. He was the first Black man to be ordained as a Moravian minister.

To provide for his family, Buckley became a teacher and assistant preacher in Greenbay, Antigua. The missionaries he worked for were fully satisfied at his service because he displayed a hardworking and devoted spirit.

As an eloquent and popular preacher, the Chapel could no longer accommodate the number of visitors who attended his services. In 1855, Buckley raised enough money within six months to enlarge the Greenbay Chapel, and he was ordained on January 3, 1856.

He created a religious school where young ones were educated but was disappointed when they refused to join the church out of fear of its discipline. Rev. Buckley cared about the welfare of his members and provided shelter for more than 100 people in the schoolroom for two weeks when a severe hurricane hit the island in August of 1871.

Rev. Dr. Eugene St. Clair Callender, the son of immigrants from Barbados, was born on January 21, 1926 in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He was a well known American pastor and an activist who was actively present in the civil rights movement.

Callender was privileged to attend his higher education in prominent colleges such as Westminster Theological Seminary and New York Law School. He was renowned as the first African American to study at Westminster.

He was ordained as the first Black minister in the Christian Reformed Church in North America while serving as the deputy administrator of the New York City Housing and Development Administration. By the late 1950s, he established Addicts Rehabilitation Center, a drug program in Harlem. A longtime senior minister and chief executive of the Church of the Master (Morningside Avenue near 122nd Street), he was also a past executive director of the New York Urban League and a former president of the New York Urban Coalition.

In the 1960s, he accompanied Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. on civil rights marches in the South. He also established, under the aegis of the Urban League, a chain of more than a dozen street academies for Black and Hispanic high school dropouts, and founded the Harlem Preparatory School, intended to further prepare Street Academy graduates for a college education.

In 1970, Rev. Callender hosted the hour-long weekly WNBC-TV series Positively Black, featuring Black artists, writers, actors, musicians, sports figures and activists, and news about life and culture in the community.

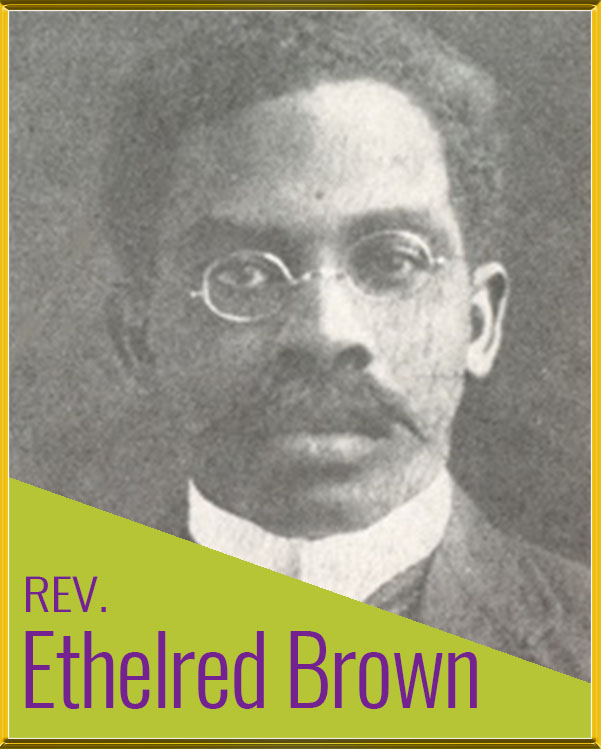

Rev. Egbert Ethelred Brown was born on July 11, 1875. He was a Jamaican-born American Unitarian minister, the founder of the Unitarian Church in Harlem as well as the forerunner in promoting the independence of Caribbean nations and liberal religion during the Harlem Renaissance.

He became fully involved in the ministry after losing his Civil Service job after working for more than 10 years. Then he decided toseek training as a Unitarian minister while working as an accountant to support his family. He subsequnently enrolled at the Meadville Theological School but received a pessimistic review by the president since there were no Black Unitarian congregations. Notwithstanding, he persisted in his training and in June 1912 was ordained a Unitarian minister.

He spent the next 8 years in Montego Bay and Kingston, attempting to establish Unitarianism there. Aside from his church pursuits, Rev. Ethelred Brown actively addressed the social and political issues in his community by organizing two civil rights organizations: the Negro Progressive Association and the Liberal Association in Kingston. He combined his activism and ministry with core concern in racial equality and civil rights.

The American Unitarian Association withdrew financial support in 1915 and in 1920, Rev. Brown moved to New York City. He founded the Harlem Community Church at 149 W. 136th Street, which became Harlem Unitarian Church in 1937.

For more than 30 years, Rev. Brown maintained a forum for debate and a social and spiritual gathering place for Afro-Americans and Afro-Caribbeans, through the Harlem Renaissance, the Depression, World War II and the early 1950s. He endorsed the politicization of his community and interdenominational harmony.

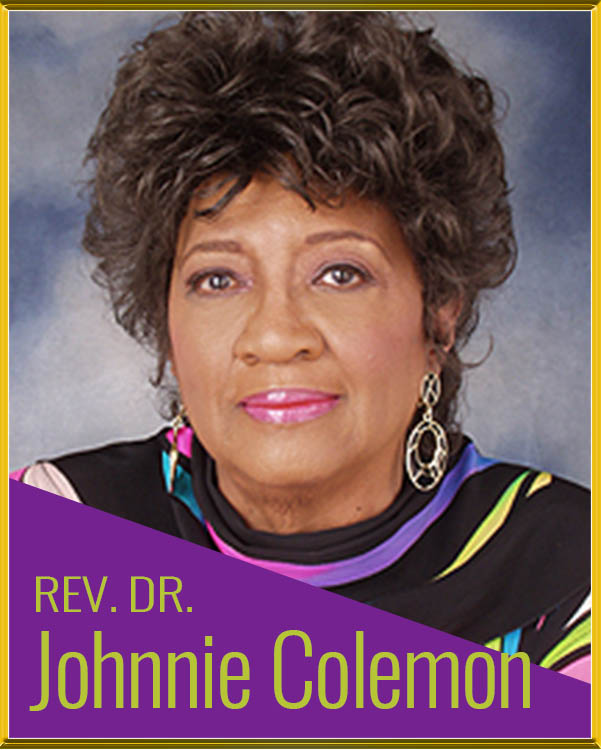

Rev. Dr. Johnnie Colemon was born on February 18, 1920 in Centerville, Alabama. She’s popularly known as the “First Lady of New Thought”, founding several large organizations within the African American New Thought movement, including Christ Universal Temple (CUT) and the Universal Foundation for Better Living (UFBL).

In 1956, Reverend Colemon was the third Black student ordained as a Unity minister from the Unity School of Christianity. Achieving this was not a piece of cake but she maneuvered the challenges of racial discrimination and successfully accomplished her purpose of attending the school.

Rev. Colemon founded Christ Unity Temple (later Christ Universal Temple), a Chicago-based church that became the largest and one of the most influential churches in Chicago. When built, it became the first megachurch on Chicago’s South Side. She was a builder and a teacher – she built 3 churches, two institutions of learning, and a restaurant and banquet facility.

Her civic positions include Director of the Chicago Port Authority and Commissioner of the Chicago Transit Authority Oversight Committee. The Candace Award was given to her in 1987 from the National Coalition of 100 Black Women and she was also honored by DuSable Museum as an African American History Maker.

by Jay Ed Styles, Senior Correspondent